Forty years after the United States began its experimentation with mass incarceration policies, the country is increasingly divided economically. In new research published in the review Daedalus, a group of leading criminologists coordinated by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (which paid me to consult on this project) argued that much of that growing inequality, which Slate's Timothy Noah has chronicled, is linked to the increasingly widespread use of prisons and jails.

It's well-known that the United States imprisons drastically more people than other Western countries. Here are the specifics: We now imprison more people in absolute numbers and per capita than any other country on earth. With 5 percent of the world population, the U.S. hosts upward of 20 percent of its prisoners. This is because the country's incarceration rate has roughly quintupled since the early 1970s. About 2 million Americans currently live behind bars in jails, state prisons, and federal penitentiaries, and many millions more are on parole or probation or have been in the recent past. In 2008, as a part of an "American Exception" series exploring the U.S. criminal-justice system, New York Times reporter Adam Liptak pointed out that overseas criminologists were "mystified and appalled" by the scale of American incarceration. States like California now spend more on locking people up than on funding higher education.

In devastating detail in Daedalus, the sociologists Bruce Western of Harvard and Becky Pettit of the University of Washington have shown how poverty creates prisoners and how prisons in turn fuel poverty, not just for individuals but for entire demographic groups. Crunching the numbers, they concluded that once a person has been incarcerated, the experience limits their earning power and their ability to climb out of poverty even decades after their release. It's a vicious feedback loop that is affecting an ever-greater percentage of the adult population and shredding part of the fabric of 21st-century American society.

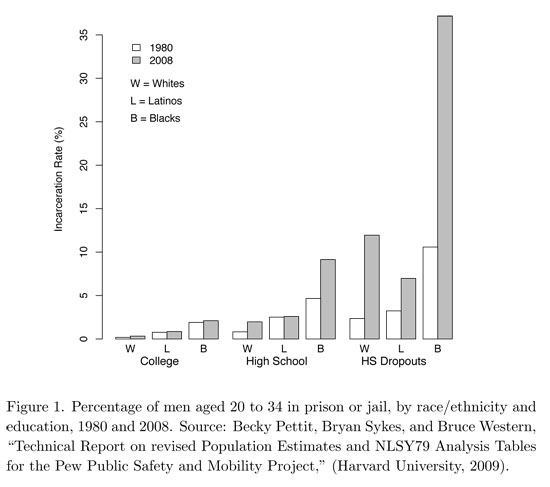

In 1980, one in 10 black high-school dropouts were incarcerated. By 2008, that number was 37 percent. Western and Pettit calculated that if current incarceration trends hold, fully 68 percent of African-American male high school dropouts born from 1975 to 1979 (at the start of the upward trend in incarceration rates) will spend time living in prison at some point in their lives, as the chart below shows.

Then, given the staggering scale of black incarceration, the authors looked at the effect on employment data if prisoners were factored into the unemployment numbers generated by the government. Using that more realistic measure of unemployment, they found that fewer than 30 percent of black male high school dropouts are currently employed. Seventy percent are jobless. Those are the sorts of unemployment figures one associates with failed Third World states rather than the largest, wealthiest economy on earth. And they augur ill for long-term social stability.

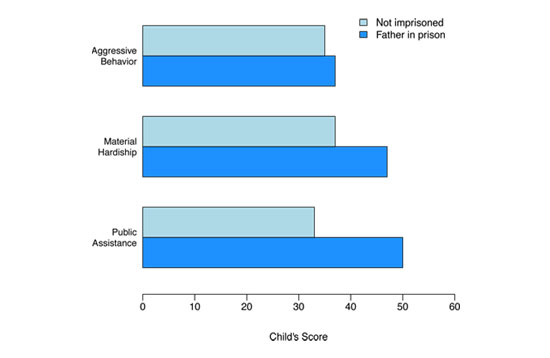

It gets uglier. When high school dropouts buck the trend by coming out of prison and finding steady work, they overwhelmingly hit a dead end in terms of earnings. Western and Pettit found that after being out of prison for 20 years, less than one-quarter of ex-cons who haven't finished high school were able to rise above the bottom 20 percent of income earners, a far lower percentage than for high-school dropouts who don't go to prison. They conclude that the ex-cons end up passing on their economic handicap, and by extension the propensity of ending up behind bars, to their children and their children's children in turn. As evidence, they cite recent surveys indicating children of prisoners are more likely to live in poverty, to end up on welfare, and to suffer the sorts of serious emotional problems that tend to make holding down jobs more difficult.

University of California at Berkeley professor of law Jonathan Simon writes that these men and women in many ways become the human equivalent of underwater homes bought with subprime mortgages—they are "toxic persons" in the way those homes have been defined as "toxic assets," condemned to failure.

Last year, for the first time since 1972, the total number of people in prison in America declined. That's a good thing. It suggests that legislators, along with the broader voting public, are finally waking up to the huge, and unsustainable, financial costs that states are absorbing by keeping large numbers of low-end offenders locked up. But the reasons for scaling back the prison system ought not to be framed solely as a cost-cutting measure that's necessary but nasty. As this new research so clearly shows, locking up poor people in historically unprecedented numbers has undermined one of America's most durable, and valuable, traits—social mobility.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário