Nick Dearden

This week has witnessed two very different reactions to European debt. At one end of Europe, Iceland's voters decided once again not to accept the payment terms of their 'creditors', the British and Dutch governments, following the collapse of Icelandic banks in 2008. At the other, Portugal is being pushed down the path of shock therapy by the European Union, with the people of that country cut out of a process which will change their lives dramatically.

Neither Iceland not Portugal will have it easy in the years ahead. But there is a world of difference between the refusal of the people of Iceland "to pay for failed banks" in the words of their President, and the pain being imposed on Portugal from the outside. The European Central Bank's head Jean-Claude Trichet has made it perfectly clear that the negotiations on Portugal's future are "certainly not for public" debate.

Iceland's people have not made a knee-jerk reaction. They are well aware that refusal to pay is the less easy short-term route to take. An impending court case by the UK and the Netherlands, the negative reaction of credit markets and the threatened block to their EU membership will all take a toll.

But for the people of Iceland the orthodoxy as to how countries are supposed to deal with debt is not simply economically flawed, it is deeply unjust, unfairly distributing power and wealth within and between societies. 28-year-old voter Thorgerdun Ásgeirsdóttir said "I know this will probably hurt us internationally, but it is worth taking a stance."

If the people of a country which truly bought into free market ideology, deregulated capital markets and cheap lending can refuse to pay for the crimes of the banks, then those that did less well from the decades of financial boom can be expected to feel even more impassioned.

In Greece such anger is starting to turn into a constructive challenge to the power of finance. A debt audit commission has been called for by hundreds of academics, politicians and activists. Such a commission would throw open Greece's debts for public examination – directly confronting the way that the IMF and European Union work behind closed doors to force their often disastrous medicine on member countries.

As Greek activists have said, "the people who are called upon to bear the costs of EU programmes have a democratic right to receive full information on public debt. An Audit Commission can begin to redress this deficiency."

Their resolve is currently being bolstered by a website phenomena – a short viral film called debtocracy (government by debt) – sweeping Greece's online population and convincing them they have been taken for a ride. Early next month activists from across Europe and the developing world will gather in Athens to put together a programme which will challenge the IMF's policies in Greece.

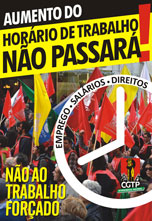

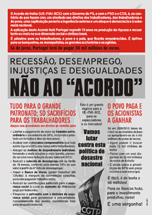

Portugal's deal is just beginning to be hammered out. As in Greece and Ireland, a 'bail-out' package will primarily benefit Western European banks, with €216 billion of outstanding loans to Portugal, while ordinary people endure a programme of deep spending cuts, reduced workers' rights and widespread privatisation. The head of Portugal's Banco Carregosa told the FT: "It's not an exaggeration to call it shock therapy."

The comparisons with developing world countries are obvious and the mistakes there are already being repeated. Time and again banks were bailed out and the poorest people in the world were pushed even deeper into poverty. Today countries from Sierra Leone to Jamaica are racking up ever more debts, once again, to weather the banker's storm.

This is why a line must be drawn in Europe. Pouring more debt on top of Portugal's woes will do nothing to resuscitate the economy. Portugal's debt is totally unsustainable – largely the result of reckless private lending over the last decade. Those responsible are being bailed out, those that aren't are suffering the pain. This is what Iceland has refused to do.

The people of Iceland have stood up for their sovereignty. Their future looks considerably brighter than those of Ireland or Portugal. The people of Greece are just beginning their struggle. The outcomes will have a monumental impact on the fight against poverty and inequality across the world.

Neither Iceland not Portugal will have it easy in the years ahead. But there is a world of difference between the refusal of the people of Iceland "to pay for failed banks" in the words of their President, and the pain being imposed on Portugal from the outside. The European Central Bank's head Jean-Claude Trichet has made it perfectly clear that the negotiations on Portugal's future are "certainly not for public" debate.

Iceland's people have not made a knee-jerk reaction. They are well aware that refusal to pay is the less easy short-term route to take. An impending court case by the UK and the Netherlands, the negative reaction of credit markets and the threatened block to their EU membership will all take a toll.

But for the people of Iceland the orthodoxy as to how countries are supposed to deal with debt is not simply economically flawed, it is deeply unjust, unfairly distributing power and wealth within and between societies. 28-year-old voter Thorgerdun Ásgeirsdóttir said "I know this will probably hurt us internationally, but it is worth taking a stance."

If the people of a country which truly bought into free market ideology, deregulated capital markets and cheap lending can refuse to pay for the crimes of the banks, then those that did less well from the decades of financial boom can be expected to feel even more impassioned.

In Greece such anger is starting to turn into a constructive challenge to the power of finance. A debt audit commission has been called for by hundreds of academics, politicians and activists. Such a commission would throw open Greece's debts for public examination – directly confronting the way that the IMF and European Union work behind closed doors to force their often disastrous medicine on member countries.

As Greek activists have said, "the people who are called upon to bear the costs of EU programmes have a democratic right to receive full information on public debt. An Audit Commission can begin to redress this deficiency."

Their resolve is currently being bolstered by a website phenomena – a short viral film called debtocracy (government by debt) – sweeping Greece's online population and convincing them they have been taken for a ride. Early next month activists from across Europe and the developing world will gather in Athens to put together a programme which will challenge the IMF's policies in Greece.

Portugal's deal is just beginning to be hammered out. As in Greece and Ireland, a 'bail-out' package will primarily benefit Western European banks, with €216 billion of outstanding loans to Portugal, while ordinary people endure a programme of deep spending cuts, reduced workers' rights and widespread privatisation. The head of Portugal's Banco Carregosa told the FT: "It's not an exaggeration to call it shock therapy."

The comparisons with developing world countries are obvious and the mistakes there are already being repeated. Time and again banks were bailed out and the poorest people in the world were pushed even deeper into poverty. Today countries from Sierra Leone to Jamaica are racking up ever more debts, once again, to weather the banker's storm.

This is why a line must be drawn in Europe. Pouring more debt on top of Portugal's woes will do nothing to resuscitate the economy. Portugal's debt is totally unsustainable – largely the result of reckless private lending over the last decade. Those responsible are being bailed out, those that aren't are suffering the pain. This is what Iceland has refused to do.

The people of Iceland have stood up for their sovereignty. Their future looks considerably brighter than those of Ireland or Portugal. The people of Greece are just beginning their struggle. The outcomes will have a monumental impact on the fight against poverty and inequality across the world.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário